A question came up in conversation at this years Board Game Studies colloquium about gaming the Crusades and specifically about the problem of simulating in a game the different objectives of the factions among the Crusaders; objectives which shifted and changed during the course of the First Crusade. A number of games have addressed the events of the Crusades, and a number of other games have offered possible models for simulating more complex objectives and victory conditions in multiplayer games.

The Crusades was an issue game in Strategy and Tactics magazine in issue 70. The game had two scenarios, a fairly simple one for the Third Crusade and a multiplayer scenario for the First Crusade.

In that scenario there are seven players, three Muslim and four Crusader, and each player chooses their own victory conditions based on controlling cities. According to case 26.3 early in the game each Crusader player chooses eight of the cities on the map which represent his victory conditions: he gets victory points for those cities and only those cities and loses points for failing to control cities which she has nominated on his list. This list is not kept secret until the end of the game but is revealed to the other players about 2/3 of the way through the game. This opens the way for a whole range of interesting diplomatic negotiations between the four Crusader players both before and after they reveal their victory conditions. As a means of stimulating different goals among the loose coalition of Crusaders this was a novel and innovative mechanism and also made for interesting gameplay.

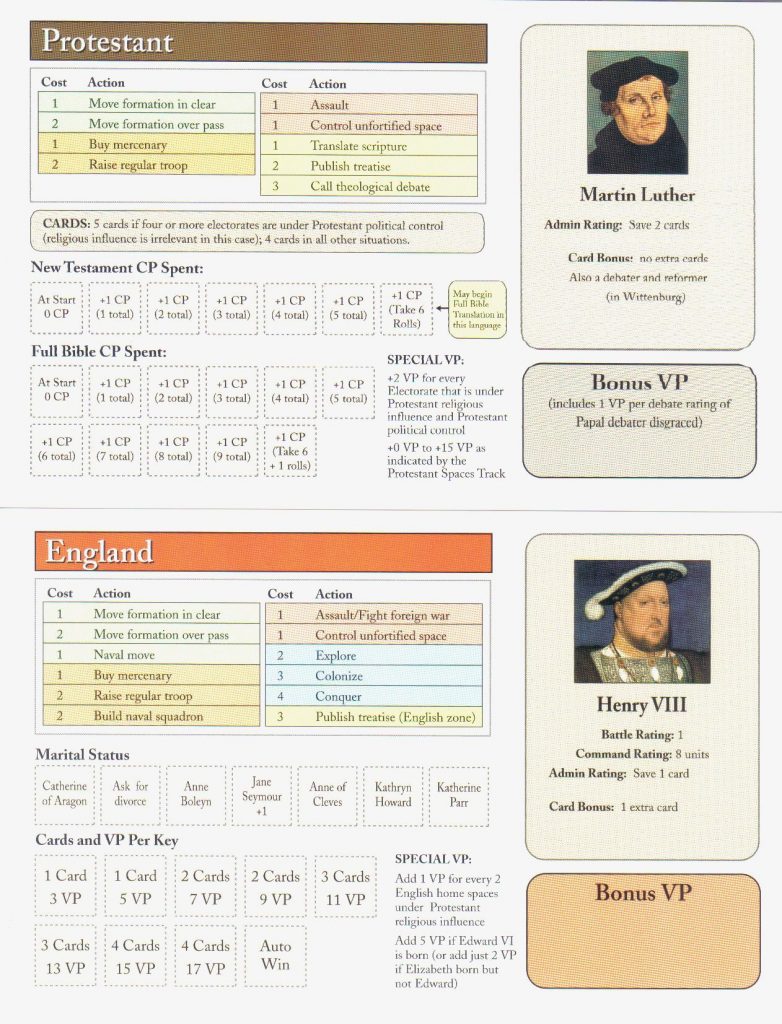

A different method of exploring alternative aims is to be found in Here I Stand, a high-level simulation which models the reformation in Europe. In the game each of the six players gains victory points for control of key fortresses but also has individual ways of accruing victory points. For example, The French player gains victory points for building chateaux , the Ottoman player for conducting piracy in the Mediterranean, the English player for securing the succession through the birth of a male heir, the Protestant player games victory points for translating the new Testament and eventually the whole Bible into German French and English. The Protestant in the player also games victory points for converting spaces on the map to Protestantism. This becomes interesting because spaces converted to Protestantism in England count for victory points for both the Protestant player and the English player. This means that in pursuing victory by conversion the Protestant player may inadvertently push the English player over the line to victory.

In Falling Sky, a game which models the Gaelic revolt against Caesar, there are four main factions the Romans, obviously, and the Belgae, the Aedui and the Arveni.

Each Gallic faction has special abilities linked to their victory conditions. Thus the Arveni can entreat, devastate or ambush well the Aedui can trade, suborn or ambush.

These games were designed as conventional war games or as modern counterinsurgency games. In all of these territorial control is a key element and in the design of the game a conventional map is the main playing space. Churchill is a more recent design which primarily aims to model the diplomatic interactions of the grand alliance during World War II. On the game board for Churchill, the territorial world map is very heavily simplified while the critical elements of the game are represented by a round table on which the three players contest in and negotiate their differing war aims. The outcome of these negotiations then feeds into the highly abstracted military campaigns between each of the major conferences. The balance therefore in Churchill has more moved from having the different objectives almost as an add-on to the conventional military campaigns to placing those objectives at the heart of the game. A number of other games are in design which explore this type of issue in more details including games modelling the Franco British struggle during the 18th century and the negotiations around the Treaty of Versailles after World War I.

In all of these games the number of variations on the victory conditions, and the special abilities of the different factions which maybe links of them, are quite limited. Undoubtedly in digital games like Europa Universalis, or Crusader Kings the algorithms which measure victory can be much more complex. However in this case complexity does not equate to realism in terms of modeling human action in history. I would argue that most historical actors conceive of a limited number of levers of power which they regard as critical and also focus on a small number of key factors which they would regard as indicators of success. This is an assertion which would need to be substantiated by exploring the world view of the historical actors in these cases in order to determine how many factors they weighed on a regular basis as critical determinants of success or failure, but I am willing to hypothesis that a board game like Here I Stand or Falling Skies probably goes far enough in terms of modelling factional political aims as is practical based on the data upon which we must build a model.

The question therefore with regard to modelling any situation where members of a given side have differing factional objectives in a boardgame is not so much one of “Can we do it?” because clearly we can, but how can we best to do it? It’s an interesting question and I feel inclined to explore it further.

Leave a Reply